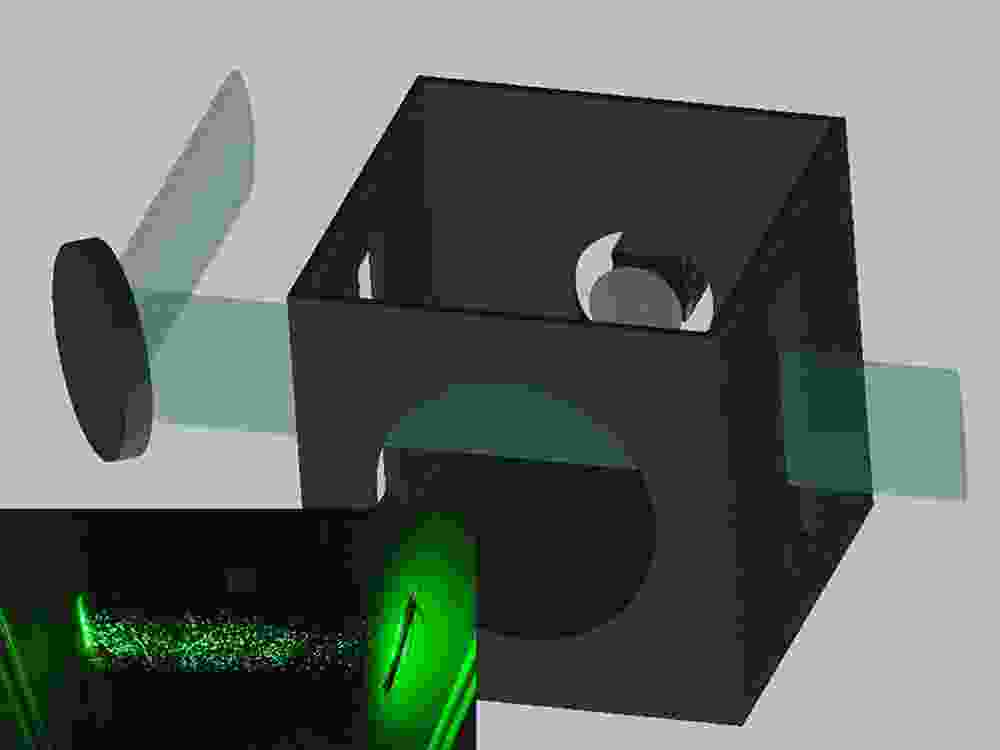

Article content continued

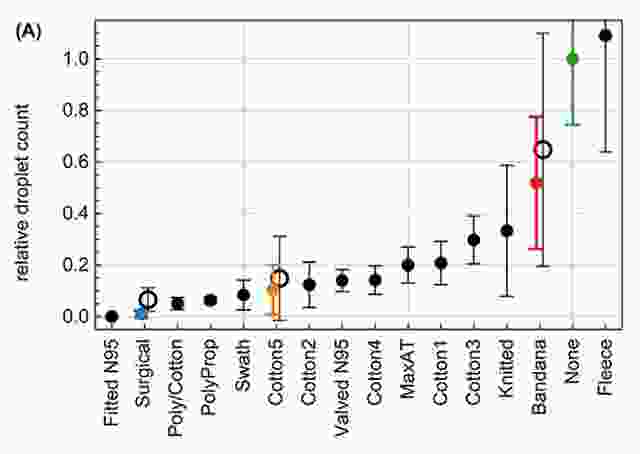

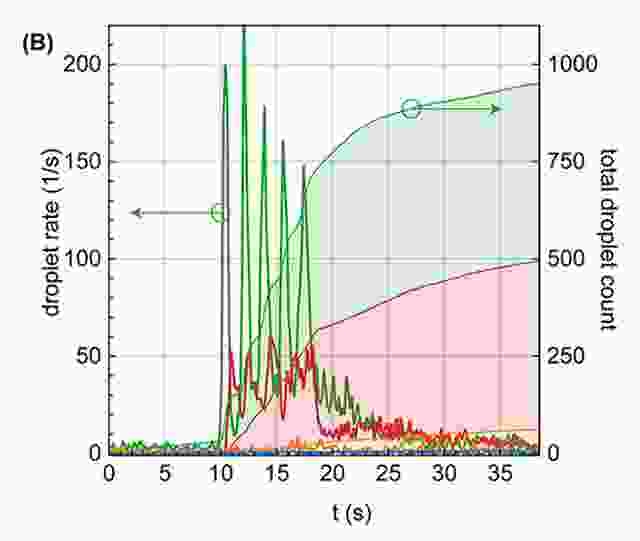

The study confirmed that N95 masks without valves are most effective at stopping the spread of COVID-19, with just 0.1 per cent of droplets escaping compared to the same speaker with no mask. Surgical masks came in second with one per cent. However, given that these masks are needed most by hospital workers, the researchers also looked at a variety of homemade masks and other common face coverings.

The study found that many homemade masks perform well. A polypropylene/cotton blend mask released just five per cent of droplets and most of the pleated cotton masks tested released less than 20 per cent of droplets. But the results varied, proving the need for more testing of commonly worn face masks, the researchers said.

A knitted mask provided less protection than any of the cotton ones and a bandana only cut the number of droplets in half. Surprisingly, a fleece neck gaiter actually increased the number of droplets expelled to 110 per cent.

“We attribute this to the fleece, the textile, breaking up those big particles into many little particles. They tend to hang around longer in the air, they can get carried away easier in the air, so this might actually be counter-productive to wear such a mask,” Fischer said in a video released by the university.

“We certainly encourage everyone to wear a mask, but we want to make sure that when you wear a mask and you go to the trouble of making a mask, you make one, or wear one that actually helps not just you, but helps everyone.”

The idea for the study came after Eric Westman, an Associate Professor of Medicine at Duke University, started working with a local non-profit to provide free masks to people who need them, according to a university press release.

“If everyone wore a mask, we could stop up to 99 per cent of these droplets before they reach someone else,” Westman said. “About half of infections are from people who don’t show symptoms, and often don’t know they’re infected. They can unknowingly spread the virus when they cough, sneeze and just talk.”