There are ethnic disparities in relation to two key indicators of the quality of HIV care, but there are no differences in viral suppression within a year of starting treatment, Dr Rageshri Dhairyawan told the virtual British HIV Association (BHIVA) conference yesterday. Although the differences are not large, dealing with them is necessary if the UK is to end the HIV epidemic without leaving anyone behind.

She said that there has been a paucity of data on ethnicity and HIV outcomes in the UK. The study’s aim was to investigate whether there are differences in outcomes in the care continuum by ethnic group amongst heterosexual men and women. Data came from 12,302 heterosexual men and women attending 25 clinics that participate in the UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) between 2000 and 2017. There was a total of 85,846 person years of follow-up.

The majority of participants were Black African (7919 people) and the second largest group was White (2345 people). Other groups were Black Caribbean (773), Black other (449), South Asian/Asian (401) and other/mixed (415).

Overall, 48% of participants were male, with some variation by ethnic group. At study entry, the median CD4 count was 276 (highest in White participants and lowest in Asian participants) and the median age was 37.

Four clinical outcomes were compared in the different ethnic groups. For each, the results were adjusted to take account of factors that could influence the results, including age, sex, having had AIDS, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, CD4 count and viral load. However, as the database does not record socioeconomic factors, these could not be taken into account.

Engagement in care was measured using the REACH algorithm, which assesses each month whether a person is ‘in care’ or ‘out of care’, based on the individual’s clinical situation and when they would be expected to next attend. A person with an unsuppressed viral load would be expected to visit the clinic within two months, whereas a patient who is stable on treatment would only need to attend every six months to be considered ‘in care’.

Participants spent 80% of their time in care. After adjustment for confounding factors and in comparison with White patients, Black African patients were 30% less likely to be in care, Black Caribbean patients 26% less likely and those whose ethnicity was mixed/other 22% less likely.

However, there were no differences in the rate of starting HIV treatment by ethnic group.

Seventy nine per cent of patients were virally suppressed (below 50) within a year of starting treatment. Importantly, there was no variation in this outcome by ethnic group.

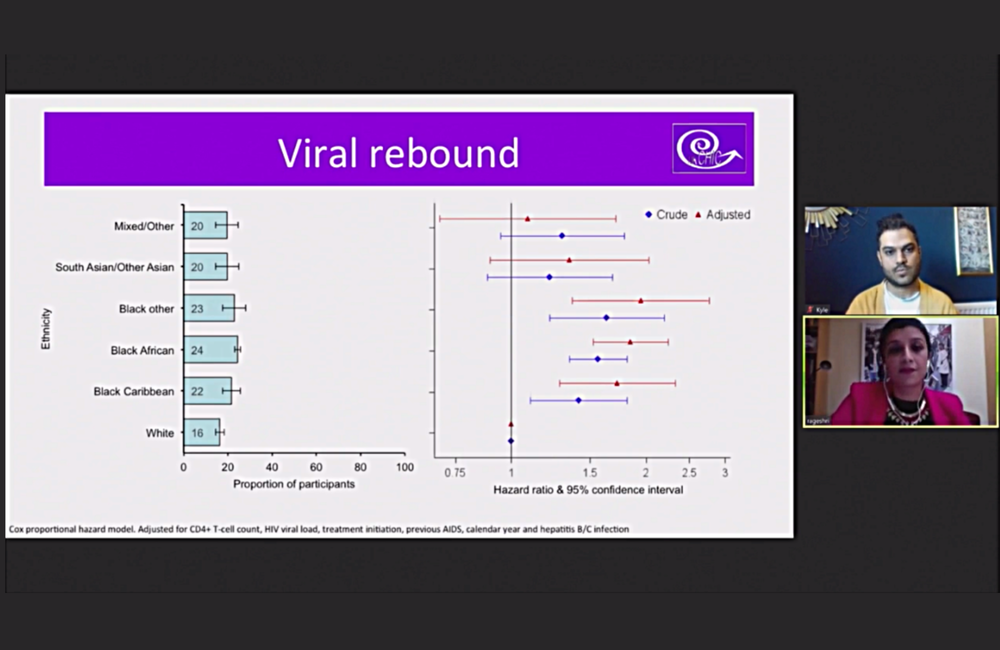

At some point following viral suppression, 22% experienced a viral rebound (two consecutive viral load results over 50). All Black groups were more likely to have viral rebound than White patients – 85% greater odds of rebound for Black Africans, 73% for Black Caribbean and 95% for Black other. There was a trend for Asian participants and those of other/mixed ethnicity to have a greater risk of viral rebound, but the results were not statistically significant, perhaps due to the smaller number of participants.

Dhairyawan said the results showed that Black and minority ethnic groups may need additional support to stay engaged in care and on treatment. Clinics should be proactive in signposting and referring patients to advice and community services for help with issues such as benefits, housing and immigration. Within the clinic, they should ensure they have access to interpreters and are informing migrants about their entitlement to NHS care.

References

Dhairyawan R et al. Antiretroviral treatment uptake and outcomes in heterosexual people living with HIV in the United Kingdom according to ethnic group. British HIV Association conference, abstract O1, November 2020.