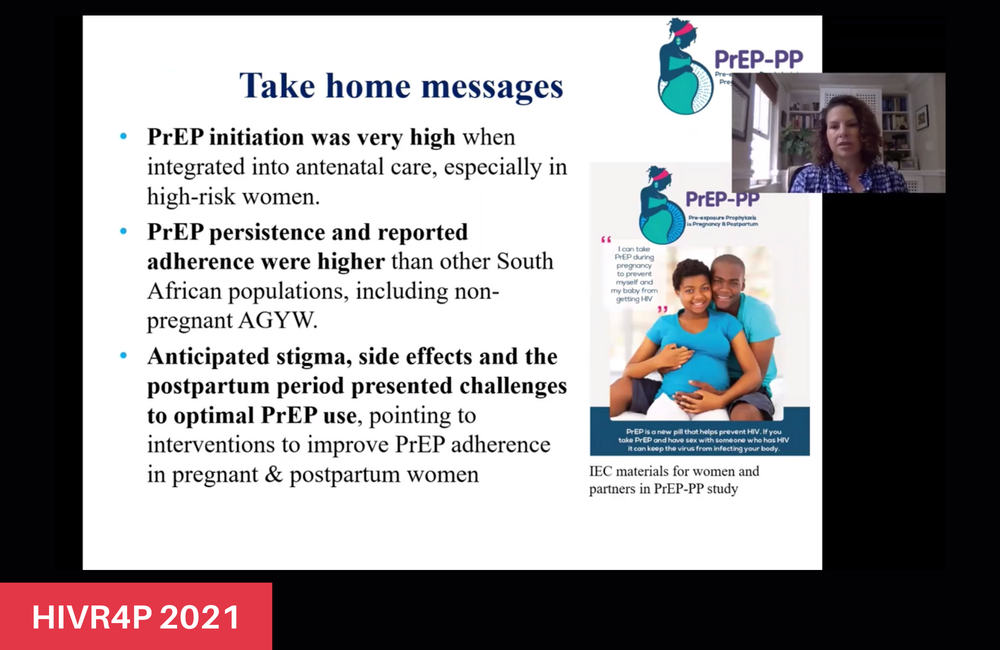

High initiation and persistence on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been documented in pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa, with 91% of those offered PrEP starting it and nearly half of those continuing to take PrEP six months later. While women who had given birth and those reporting side effects were less likely to stay on PrEP, there was a strong desire to avoid HIV infection for themselves and their infants, especially when their partner’s serostatus was unknown.

HIV incidence is high in pregnant and breastfeeding women in South Africa, with a third of all infant infections due to acute infections in the mother. More than 76000 new cases of HIV infection in infants are expected over the next decade as a result of vertical transmission.

While oral PrEP is safe and effective at reducing HIV acquisition during pregnancy and breastfeeding, high adherence is required at the time of potential exposure – especially during pregnancy, when tenofovir plasma concentrations are lower than in the period after birth.

The study

Dr Dvora Joseph Davey and colleagues recruited 712 HIV-negative pregnant and breastfeeding women aged 16 and older from a community health centre in a diverse urban township with high HIV incidence in Cape Town. After receiving HIV counselling and being offered PrEP at antenatal visits, these women were followed for a year after giving birth. The women did not need to take PrEP to be enrolled in the study and could start and stop PrEP at any time during the study.

The women’s median age was 26, with a median gestational age of 21 weeks. A large majority reported sexual activity during pregnancy (98%), with over half of the women not married and not living with their sexual partners. Most of the women had previously tested for HIV (73%) and few reported having partners living with HIV (2%) or more than one sexual partner in the past year (2%). Other risk factors included reports of intimate partner violence (14%) and alcohol or drug use (48%) in the past year. Just over a third of all women were diagnosed with an STI, with chlamydia being most frequent. Less than a quarter of women had heard about PrEP prior to this study.

The researchers also collected additional qualitative data from 25 in-depth interviews with women who had given birth. They had taken PrEP in the month prior to the interview and during pregnancy. The median age of this subset of participants was also 26 (ranging from 16 to 43 years old), they had been on PrEP for a median of nine months, with a median time of 18 weeks since giving birth.

PrEP initiation

The large majority of women who were offered PrEP chose to start taking it (91%). While this varied on a month-to-month basis, over two-thirds of all women enrolled every month opted to take the PrEP that was offered to them.

While diagnosis of an STI was a facilitator of PrEP initiation (93% of those with an STI started taking PrEP), being married (only 67%) and reporting stigmatising views towards PrEP use (only 56%) proved to be barriers to PrEP initiation.

Interviews revealed that women wanted to take PrEP because of their partners’ potentially risky sexual behaviour, unknown HIV status and because they wanted to ensure that their infants were born without HIV.

“Even if you sleep with your partner without protection [condoms] or if you don’t know what he is up to, if you use PrEP, you know you are safe. That is the main reason that made me take PrEP… He loves girls; he is not trustworthy.”

“It [PrEP] is protecting the unborn baby. It was very important that I protect the baby. I knew I was negative, so I didn’t know what the situation would be when the baby came.”

PrEP persistence

Persistence was defined as returning for a repeat PrEP prescription after baseline initiation. As expected, this was highest one month after starting PrEP (74%) and steadily declined over time (68% at month three; 48% at month six). However, as part of the study coincided with the strict COVID-19 lockdown in South Africa, a steeper decline was noted during this period. Additionally, women were less likely to return for PrEP refill after giving birth.

Partner support emerged as a crucial factor to encourage women taking PrEP during pregnancy:

“I was concerned that my partner will tell me about the child… taking a pill during pregnancy and how can I trust them [the pills]. But I decided to be courageous and tell him because he will find out, he will see it on the [clinic] card. Luckily, it was received by someone who understood it. I told him about it the way I was told… He was not stubborn and said I should continue.”

PrEP adherence

For those attending clinic visits, PrEP adherence was reported as taking PrEP for five days or more in the previous seven days. Self-reported adherence was high: 87% of women on PrEP reported good adherence at the one-month clinic visit and 85% did so at the three-month clinic visit. However, women who had given birth had much lower odds of reporting persistence and adherence, when compared to pregnant women (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.31). The results from an objective measure of adherence – dried blood spot tests – were not available at the time of this presentation.

Factors associated with poorer PrEP persistence and adherence included higher gestational age at first visit (greater than 20 weeks, aOR = 0.57), lower levels of education (aOR = 0.51) and reported side effects (aOR = 0.50).

Women who disclosed their PrEP use to family, partners and friends were more likely to remain adherent, as described in the interviews:

“[My mother] said I should take it [PrEP] because it is not nice to have something you didn’t ask for [HIV]. I should take the pills and I should not mind anyone who says I have HIV.”

“My sister was happy for me. She said it was the first time she was hearing about it, but said it sounded interesting when I explained it… she said I should continue.”

PrEP continuation after birth

“PrEP is protecting the unborn baby. It was very important that I protect the baby.”

While some women had a period of sexual abstinence after birth (ranging from weeks to months), many of those who reported high adherence continued with PrEP after birth, as they felt empowered, safe and relieved as a result of taking it, or because it had become part of their routine.

“I had made the decision, and no one was going to stop me. I was not going to go backwards.”

“The baby was fine when I had her. She didn’t have a problem. I trust that it was the pills I was taking. So I continued.”

Barriers to PrEP use included limited partner support, safety concerns, side effects and HIV-related stigma. However, many women interviewed found ways of overcoming these barriers – they developed resilience in response to these challenges.

“When I started, I was vomiting so I thought I would stop taking it, but I thought, what will I do if I stop? I changed, I was taking it in the morning. I changed and took it at night, then I was fine.”

“I was concerned that they would say it is not PrEP… Saying that I am hiding, that [the pills] are something else, that they are not for what I say they are for.”

“They [friends] listened. They opened them… They looked and asked why they look like ART [antiretrovirals]. I said I was not told that they are ART.”

“Facilitators of optimal PrEP use through pregnancy and postpartum were primarily fear of HIV acquisition for the self and the infant, mostly due to the partner’s behaviour and unknown serostatus, a strong desire to have an HIV-free infant, PrEP disclosure and encouragement, and an ability to overcome side effects and stigma,” Davey commented in conclusion.

She recommended interventions including partner/couple testing (including HIV self-testing for couples), the integration of PrEP and adherence counselling into existing antenatal and postnatal care services (including advice on managing side effects), as well as broader community education about the safety and efficacy of PrEP for pregnant women.