The first data from the large implementation study of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in England, The IMPACT trial, were presented at the joint British HIV Association and British Association of Sexual Health and HIV conference this week.

Chief Investigator, Dr Ann Sullivan of London’s Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, told the conference that although there were a number of subtle differences in the recruitment figures for different risk groups and people of different ethnicities and nationalities, the clearest evidence of inequality of access to the trial was that younger people aged 16-25 were under-represented relative to their risk of HIV, compared with older people.

The data Dr Sullivan presented was solely baseline enrolment data. Later analyses will look at HIV infections among participants during the trial, and reasons for them; evidence for population-level changes in HIV incidence and STI infections during the trial; and, derived from that and other risk calculations, the “PrEP cascade” or proportion of the English population at risk of HIV who were protected by enrolling in the trial.

The trial ran from October 2017 to July 2020. Initially there were 10,000 trial places allocated, but the obvious need for and popularity of the trial led to two expansions, with a final maximum number of 26,000 places on offer. The majority of English sexual health clinics, numbering 157, took part, with a minimum number of 20 IMPACT participants per centre.

The trial used different definitions of ‘eligible for PrEP’ and ‘at risk of HIV’. To be eligible, the primary criterion was, in gay and bisexual men and trans women, that the person had had condomless sex in the previous three months and anticipated doing so in the next three months. Another criterion was that they had an HIV-positive partner with a viral load over 200. The third, catch-all criterion was that the person was considered to be “at similar high risk” to a person with an HIV-positive partner who was not virally suppressed.

‘At risk of HIV’ was a much broader category, including all people with characteristics suggestive of HIV risk. These included people with histories of frequent HIV testing or STI checkups, people who had previously sought post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), people involved in sex work, and people referred to the clinic via partner notification.

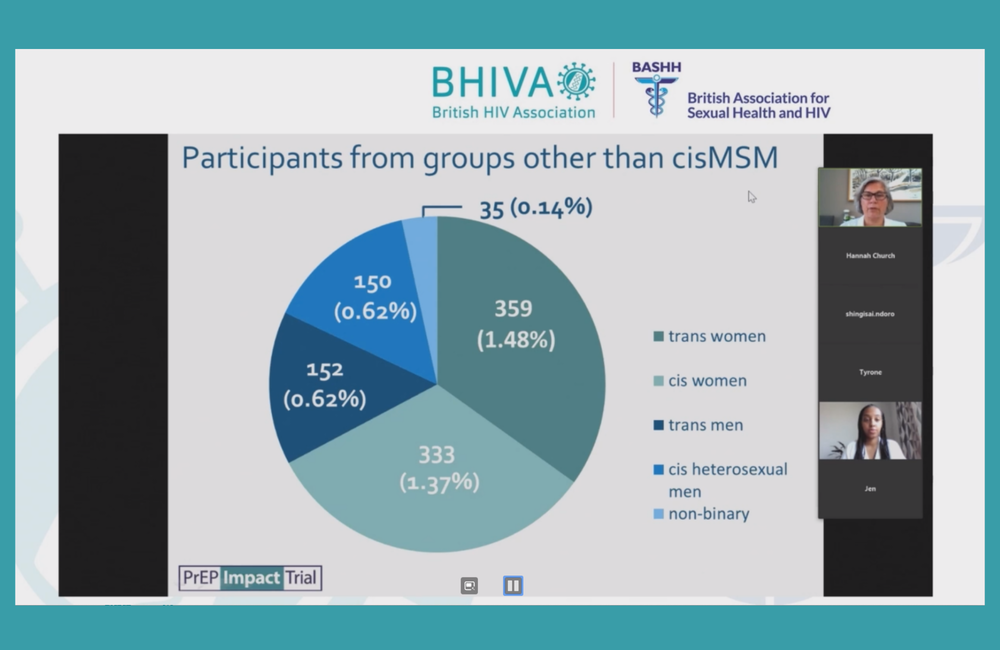

In the end, the actual number of participants was 24,255. Of these, the vast majority were cisgender gay and bisexual men. However, 1038 trial enrollees (4.3% or one in 23 participants) were not in this group.

Of these 1038, just over a third were transgender women (359) and just under a third were cisgender women (333). Twenty-nine per cent were men, evenly split between transgender men (152) and cisgender heterosexual men (150). There was also a small number of non-binary participants (35).

IMPACT offered a choice, to cisgender gay and bisexual men, of starting either on daily or on event-driven PrEP. The large majority of them (85%) opted to start on daily PrEP. In a presentation from Scotland also given at the conference, the proportion of gay men opting for event-driven PrEP increased over time; it will be interesting to see if this happened in IMPACT too.

Figures for the age, ethnicity, nationality and location of enrolees were then presented by Dr Sullivan, but these only covered the 21,357 people enrolled to the end of February 2020; the remaining 2898, enrolled during the COVID pandemic, will be analysed separately.

The median age of participants was 33, with a very wide range, from 16 to 86. The majority of cisgender gay and bisexual men were aged 25 to 40. On average, cisgender women were somewhat older than other trial participants and transgender women notably younger.

The majority of trial participants were of White ethnicity, including 76% of cisgender gay and bisexual men, 60% of cisgender women and 49% of cisgender heterosexual men. Limited numbers of black African people were recruited (11% of cisgender women and 19% of cisgender heterosexual men), despite the large number of HIV diagnoses in this group. Among the cisgender gay and bisexual men, the biggest single non-White ethnicity was Asian at 5%. Nearly 11% of the transgender women were Asian and very few trans women or men were of Black African or Caribbean ethnicity.

Just under a third of trial participants were born outside the UK; among the cisgender gay and bisexual men, 30%. But a considerably higher proportion of trans women (40%) were born abroad. Among this group and the cisgender heterosexual men, the majority born abroad were non-White, but in other groups the majority were White.

Just over 50% of trial participants lived in London, though only a minority of cisgender women and heterosexual men. Conversely, nearly 60% of transgender women lived in London and the large majority of trans women and men in London or the south; this was attributed to successful recruitment programmes at three clinics in London and Brighton.

Using the broader definition of ‘at risk’, and data both from the trial and from the broader database of sexual health clinic attendees, the researchers were able to calculate two quantities; PrEP coverage, which was the proportion of people at risk who were enrolled in the trial, and PrEP uptake, which was the proportion of those assessed to be eligible who were recruited.

“Only 8% of enrollees were in the two youngest age groups compared with 16% in the two oldest.”

Nearly all cisgender gay and bisexual men attending sexual health clinics (93%) were judged to be ‘at risk’, and 26% ‘eligible’, of whom half (13%) were enrolled. Seventy-seven per cent of trans women and 65% of trans men were at risk, and of these the large majority were eligible for PrEP; 62% of all sexual health clinic attendees who were trans women were enrolled and 50% of trans men. Conversely, only 5% of cisgender heterosexual male clinic attendees were judged to be at risk of HIV. People who were White and born outside the UK were more likely to be at risk of HIV, and not because they were cisgender gay men; they formed a disproportionate fraction of the other groups.

However, the biggest discrepancy in both coverage and uptake was between age groups. Only 8% of enrollees were in the two youngest age groups compared with 16% in the two oldest. Considering cisgender gay and bisexual men alone, it was estimated that just 9% of all those at risk aged 16-19 were enrolled in the study, compared with 28% of those aged 45-49 (coverage). Just 38% of those assessed as eligible aged 16-19 were enrolled, versus 67% of those aged 45-49 (uptake).

Asked about the reason for this under-representation of young people, Dr Sullivan said that younger people might be less knowledgeable about PrEP and about sexual heath generally. They might be more reticent about disclosing sexual behaviour, especially if clinicians do not ask them direct questions.

Paradoxically, however, this may lead to an over-estimation of risk if clinicians make assumptions about young people’s behaviour rather than asking them direct. This would tend to inflate the number of young people considered to be at risk compared with older people. The key was to train clinicians to put young people at ease and talk openly about their risks, or lack or risk, of HIV and STIs.